Tahitians said artifacts from their past called out to Dr. Yosihiko Sinoto, that he caused them to reveal themselves. The Bishop Museum’s eminent archaeologist, Dr. Sinoto, passed away in October this year, leaving behind a legacy of ground breaking scholarship, dedicated preservation, and friendships across the Pacific. HPR’s Noe Tanigawa checked in with Dr. Sinoto’s son and a colleague for insights into the man and his work.

The Bishop Museum honors Dr. Yosihiko Sinoto this Thursday, 12/28/17, starting at 10am on the Great Lawn, with traditional kite flying expected in the afternoon. A book length interview with Dr. Sinoto, Curve of the Hook: An Archaeologist in Polynesia, has been published by University of Hawai‘i Press. Its first printing is nearly sold out.

Archaeology researcher Eric Komori says uncovering Hawai‘i’s material remains got off to a slow start in Hawai‘i because of a belief that Hawai‘i was too young and the environment not favorable for preservation. That is, until a discovery in a Kuli‘ou‘ou cave in 1950.

Komori: Kenneth Emory with his students were digging a rock shelter there and found some charcoal at the base of a fire pit in the shelter. Astoundingly it came out to be, I think 500years old. No one thought people had been living here that long. It was a big revelation for everyone. It is worth doing excavations in Hawai‘i and it can be very, very interesting.

Archaeologist, Dr. Yosihiko Sinoto credited Dr. Emory with “kidnapping” him in 1954, introducing him to Pua Ali‘i, a site in the dunes above the cliffs at South Point. Without pottery, traditionally a key indicator, Sinoto began a search for other means to establish dates and relationships. His family soon joined him in Hawai‘i, and Dr. Sinoto began a much decorated 60 year tenure with the Bishop Museum. Dr. Sinoto’s son, archaeologist Akihiko Sinoto,

Sinoto: Since he started in Hawai‘i, the question he asked himself is, Hawai‘i is an isolated group of islands in the middle of the Pacific, How did people get here? That was the crux of his research.

The search for those origins took Dr. Sinoto to the Marquesas and the Society Islands for ground breaking discoveries.

Sinoto: The first thing he would do, he called it in his own words, prospecting. He would get to an island and he’d walk it.

Dr. Sinoto would walk the entire island looking for good places to live. On an island those spots would be coastal flats, into valleys, where people usually live still. Shell or bone fragments turn up. Sinoto says Tahitian land crabs burrow and basically do test excavating for you. Layers of dark then light sand are indicators of human habitation. Eric Komori worked with Dr. Sinoto for decades.

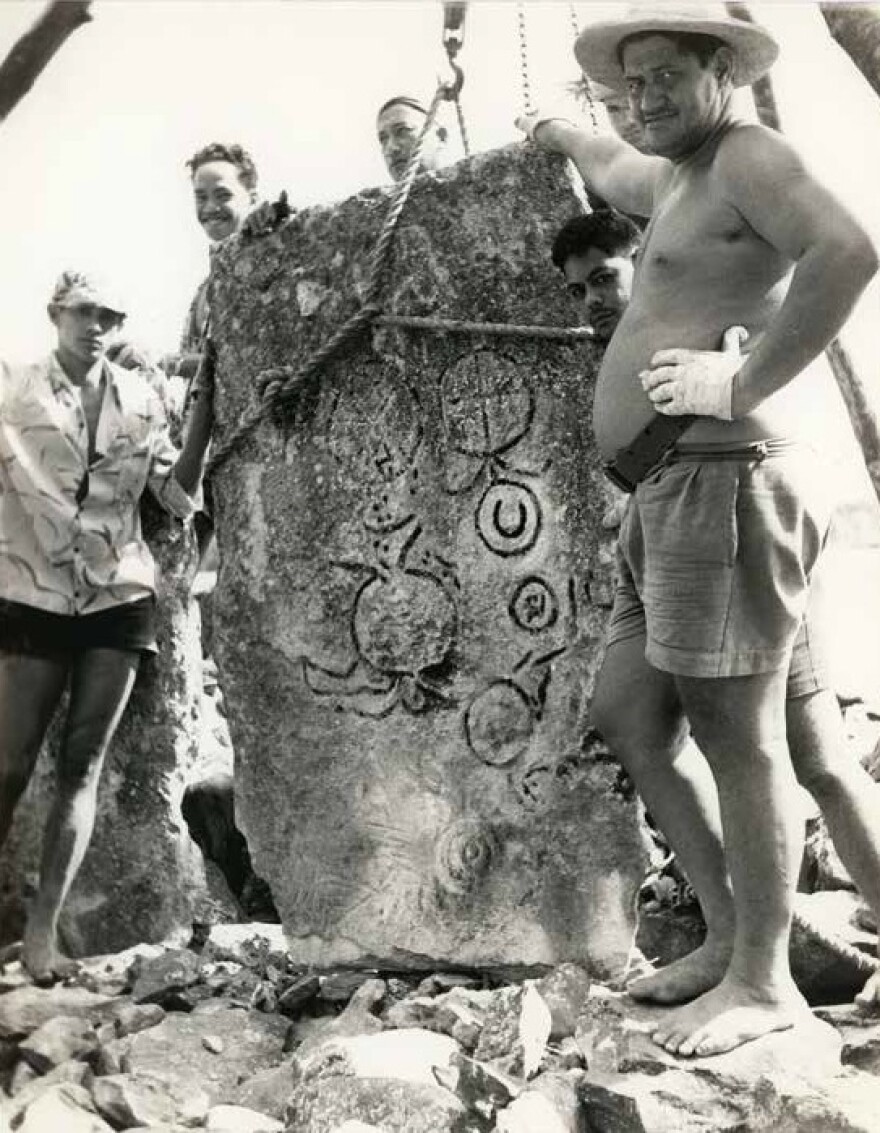

Komori: He did have something special, his powers of observation were something special. Walking around entire islands looking for potential site areas, he’d always concentrate on where there were passes through the reef, access for canoes and things like that. Some of the Tahitians said these artifacts are calling out to him because he’s always finding things.

Komori: He’d always hire local people, he was fluent in Tahitian. When he hired people, he grew very close to their families and became part of the community. In the book there’s a story about how he was accepted as a matahiapo, an elder of the village he was working on as an example of how close he came. I experienced his attention to detail and ability to concentrate under difficult circumstances because I’ve been on hikes with him where we have ten or twenty people in forests or jungles. Everyone’s looking for sites and things.

Komori: He always would trail in the back of the group. Often you’d hear him say, Just a moment, please.

We’d look back and he’d be pointing at something on the ground like a petroglyph on a rock or some artifacts, fish hooks on the side. He was seeing things at a different level.

Sinoto: He always made it a point to talk to the local people too because he knew they had knowledge he didn’t have. He worked in Tahiti for decades, three or four years ago when he went back, they finally told him, Oh now we know why you did this for so many years. So he was happy, he was really happy.

Today’s work on the past is for the future, that was the message. Dr. Sinoto worked tirelessly to ensure people an accurate picture of the past, fighting the pastiche of cultural signs that can be marketed as authentic.

Dr. Sinoto’s breakthrough revolved around Polynesian fishhooks. Their curvature, the head of the hook, their carvings, notches or knobs, provided cultural links the way pottery does in other locales. Through tracing fishhooks as part of a group of cultural markers, Dr. Sinoto postulated early settlers went from the Marquesas to the Society Islands and from there to Hawai‘i. His discovery of an ancient double hulled canoe in the Marquesas was the first material documentation of early Polynesian voyaging. But why did they come to Hawai‘i? Sinoto says there are theories that forces at home drove Polynesians to other lands.

Sinoto: My father’s theory has always been, it’s human curiosity. When they were out doing pelagic fishing, obviously the fishermen would have seen birds coming from a different direction. Why are those birds coming from there and not from behind us? That must mean there might be islands out there. The H?k?le‘a has showed the ancient navigators had a much better feel for the ocean, the winds, and the stars than we do today. He thinks the very first voyaging took place because of curiosity.

Dr. Sinoto ultimately believed in people. And he believed in museums to preserve and perpetuate human achievement. This week, the Bishop Museum welcomes nearly 70 community elders from Huahine, an island where Dr. Sinoto’s work is ongoing. They will honor his legacy with traditional kite flying, huge kites. Dr. Sinoto revived them in the 1980’s and it has become a competitive sport.

Dr. Sinoto received a number of awards, including Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays; a Tahitian knighthood (the Order of Tahiti Nui, Chevalier); the Society of Hawaiian Archaeology’s Naki‘ikeaho Cultural Stewardship Award; and Bishop Museum’s Robert J. Pfeiffer Medal. He received a lifetime achievement award from the Historic Hawai‘i Foundation and was named a Living Treasure of the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawai‘i. His life and legacy are chronicled in Curve of the Hook: An Archaeologist in Polynesia. Published first in Japanese, it became an award winner, now translated to English and published in September 2016 by University of Hawai‘i Press.