A major hurricane that hit Hawai?i in the nineteenth century is changing our understanding of hurricane risk in the islands. While minimal reference exists in English language sources, the event was well-documented in Hawaiian newspapers of the time. HPR Reporter Ku?uwehi Hiraishi has more.

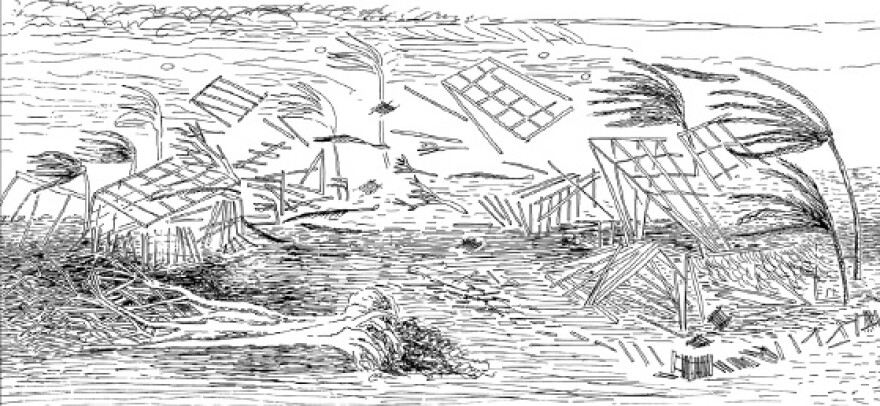

On August 9, 1871, a major hurricane struck the Islands of Hawai?i and Maui, causing widespread destruction from Hilo to Lahaina. Eyewitness accounts were sent in from Waipi?o, Kohala, H?na, and Wailuku, and were published in Hawaiian language newspapers.

“That’s happening in all newspapers, all the time. People wanna hear what’s happening in K?pahulu, what’s happening in Kaua?i,” says Puakea Nogelmeier, “The newspapers are seen as a national tool.”

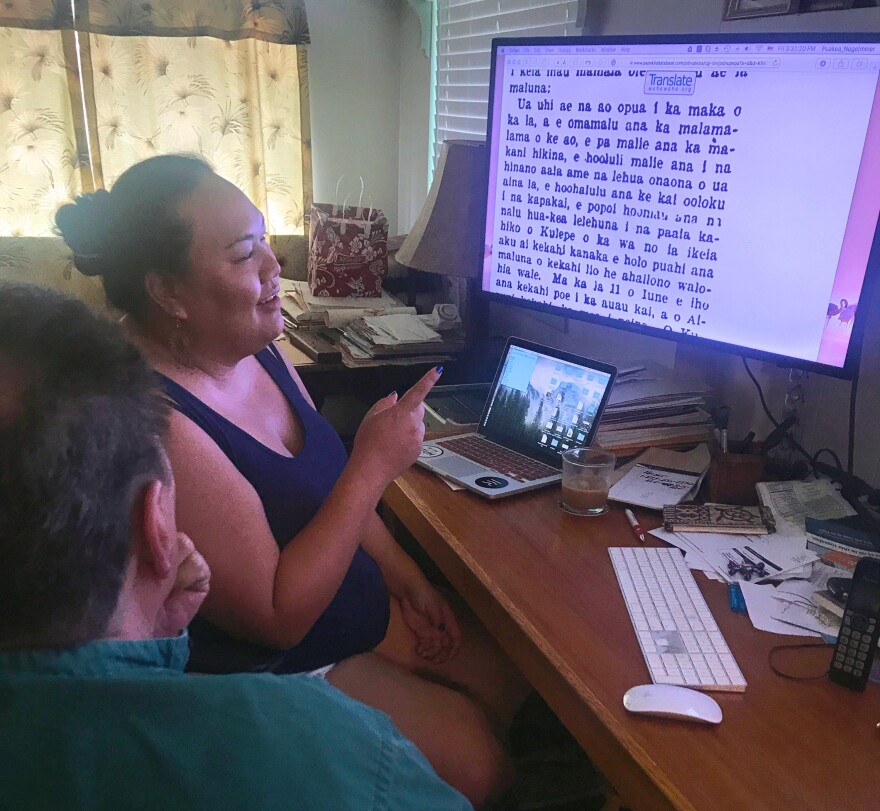

Nogelmeier is the director of the University of Hawai?i Institute of Hawaiian Language Research & Translation. He led a team of graduate students in compiling a digital database of more than 4,000 Hawaiian language newspaper articles related to meteorology and geology.

“I've been looking at basically like natural disasters but looking specifically at seismic activities so earthquakes, volcanic eruptions as well as tsunamis,” says Paige Okamura.

Okamura is a graduate research assistant with the Institute working on her master’s in Hawaiian Language at UH M?noa. She and Nogelmeier go over her translation of an article line by line.

“You have these extremely detailed...I think we'd call it citizen science reports,” says Okamura, “So it kind of reminds us that our kupuna were expert observers of their environment. It's not something that we forgot, it's just a nice reminder.”

Professor Steven Businger chairs the University of Hawai?i at M?noa’s Atmospheric Sciences Department. He was the lead author on a paper on the 1871 hurricane recently published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

“To get the details, the blow-by-blow location and time of what happened in this storm, the impact of this storm back in 1871 – before television, before radio...it was just amazing to me,” says Businger.

He was able to extract scientific data from the citizen science reports translated by students like Okamura.

“And you can run the data in a scientific way and say well, in order for winds to be strong enough to knock over these kinds of trees you need X amount of gale force winds,” says Okamura.

“Knowing that this was a category 3 hurricane at least, maybe a category 4 hurricane that made a direct hit on the Big Island and also impacted Maui severely – that was very important information for making decisions about hurricane risk and hurricane insurance,” says Businger.

He says there was a general assumption following Hurricane ?Iniki in 1992, that Hawai?i and Maui were immune from powerful hurricanes because it had been over a century since one hit. Government officials were considering removing a mandate for hurricane insurance until they came across this research.

“I think that the broader story, which is also included in the article about how literacy in Hawai?i took off back in the early 1800s, and in fact nowhere else in the western hemisphere do we have so many written materials from a culture that previously didn't have writing,” says Businger, “There?s not even a close second.”

From 1834 to 1948, more than a hundred independent newspapers were printed in Hawaiian. Only a small fraction of that has been translated.

Hurricane with a History: Hawaiian Newspapers Illuminate an 1871 Storm by HPR News on Scribd